Table of Contents

A journey in India: Walking in the footsteps of Mirabai

In October 2014, I undertook a cultural expedition to walk in the footsteps of Mirabai (also known as Mira Bai or Meera Bai), thanks to a grant from the Kensington Tours Explorers in Residence program. Mirabai was a 16th century Rajasthani princess, a composer of devotional songs and a mystic who fought against convention to give voice to her spiritual yearnings. She travelled widely in Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh in north India. On this trip to uncover the significance and mythology of Mirabai, and I traced her life through her journeys. Read on to find out more information about Mirabai, her poems, and some images.

Mirabai’s life is significant, and has relevance today, because her story parallels the struggle many women have to live a fulfilled, creative life — when society pressures them to settle down, marry and devote their lives to their domestic obligations and “duties.”

Mirabai: A symbol for women’s freedom

Mirabai was known for the incomparable beauty of the poems and bhajans she composed and sang in devotion to her beloved god, Krishna. Born in Rajasthan in 1500 AD, she was married against her will to a prince of Chittor, near the fabled city of Udaipur. Her life was marred by persecution as she struggled to manifest her ardent desire to compose, sing and pursue spiritual studies. Though she was renowned for her talent, her family felt she was bringing dishonour by not behaving the way a courtly lady should — and they tried to poison and drown her.

Mirabai escaped and travelled widely, journeying across country to Vrindavan and Mathura, playground of Krishna, and to Dwarka in Gujarat, site of an important Krishna temple. Eventually, a deputation of men from Chittor found her in Dwarka, but before they could abduct her, she disappeared while singing in the temple. All that was found was her sari, draped around the Krishna murti.

Many legends swirl around the myth Mirabai. It was said a sadhu (holy man) gave her a tiny statue of Krishna when she was a child, and that was when her love for the god was born. It was said she survived attempts to take her life through divine intervention: poison turned to nectar, a bed of blades turned to petals. It was said Emperor Akbar came to hear her, in disguise as a sadhu.

Today, Mirabai is considered one of the great female saints of India and her songs are still sung. Moreover, there have been hundreds of songs composed in her honour and there are festivals devoted to her that take place around the time of Dusshera in Rajasthan. She is still very much alive today in the hearts of Indians.

A sample of Mirabai poems

Mirabai’s poetry was unique in her day — much more straightforward, emotional, honest and vulnerable. The strength and power of her words stand to this day, a testament to her courage, love and talent.

NOTHING IS REALLY MINE

Nothing is really mine except Krishna.

O my parents, I have searched the world

And found nothing worthy of love.

Hence I am a stranger amidst my kinfolk

And an exile from their company,

Since I seek the companionship of holy men;

There alone do I feel happy,

In the world I only weep.

I planted the creeper of love

And silently watered it with my tears;

Now it has grown and overspread my dwelling.

You offered me a cup of poison

Which I drank with joy.

Mira is absorbed in contemplation of Krishna,

She is with God and all is well!

The Mirabai expedition itinerary and route

I travelled for about four weeks on my Mirabai itinerary. I started from Delhi and visited the following places, travelling by train and taxi as I went:

- The Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan, Uttar Pradesh

- Mirabai’s home (now a museum) in Merta, Rajasthan

- The Mirabai Temple, Merta, Rajasthan

- The Mirabai Temple at Chittogarh Fort, and the ruins of her palace

- The Krishna Temple in Dwarka, Gujarat, where she disappeared

The Mirabai expedition begins

It’s the first day of my Mirabai expedition and I’m feeling very vulnerable. India can cut you open.

The early morning taxi to Nizamuddin train station, leaving behind friends, leaving behind Delhi and festival time, leaving behind Ajay. Last night we walked in the park at dusk with the sounds of Ravanna burning, and bursting in fireworks, all around us. Trees filled with unseen birds making a roof of noise. The Shiv Mandir in the park delicately lit, only Panditji inside, Ajay and he finally meeting after so many years.

Sikh taxi driver in a black van with yellow stripes, the kind of Delhi taxi I know so well. First early morning India train in a long time. Very skinny people on the side of the road, wrapped in fabric, noisy chai stalls, shantis, broken pavement, a stream of litter, everything tinged red sandstone and pink sunrise.

Arrival at station and greeted by porter who demands way too much money, and I don’t have very much fight in me. He seems nicer than most, less hard, so I capitulate at an exorbitant 150 Rs, about two or three times what I should be paying. But he is going to wait with me for the train, find my car, my seat and put my bags on the rack. It’s very convenient and frankly worth the money.

We stand on the dirty, crowded platform and I watch children garbage pickers with bags slung over their backs, like small Santas, walking the tracks. They are all between 10 to 15 years old, very small, wearing torn and filthy clothes. A family sits on the ground in front of me, and the baby pees, leaving a puddle. The tiny mother, in a shiny bright yellow sari covered in glitter, lets him sit naked on the platform while she changes him.

I peel an orange and hand my porter a slice, which he accepts with a smile. He’s sitting on a stack of big sacks filled with something like rice.

Yesterday, October 2, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a nation-wide Clean India campaign on the birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. The campaign makes me notice how dirty India is like never before. There is garbage everywhere, wrappers, bottles, plastic bags, and open sewers, animal shit, red streaks of pan spittle. India is impoverished, but does it need to be so dirty? Can people change? Just as I am wondering this, a middle class man drops a wrapper on the platform about a metre from a dustbin.

The train arrives on time and I find my seat, beside a large and assertive couple. I sense they would like to spread out and take all three seats and I feel I have to fight for my space as first her elbow, and then his (after they change seats) appears in front of my face.

I try to read my book about Mirabai but it’s hard to concentrate on the flowery language, full of descriptions about her devotional fervour. I don’t feel this kind of spiritual intensity so it’s hard to imagine or grasp. Is belief an act of faith? Is it a feeling, like falling in love?

As I set out on my Mirabai Expedition to trace her route, her journeys and try and get a sense of her life, I wonder how similar we are, and how different. I was born into a kind of freedom she could never have imagined as a woman in traditional India. But I cannot imagine her religious fervour, and her courage in striking out on her own to travel the dusty roads of India.

The train ride from Delhi to Mathura Junction is only two hours, and it arrives pretty much on time. I’m hungry as I have only munched on some fruit, an Indian milk drink and a cup of railway chai — which comes in a small cup, with milk, sugar and tea bag for 7 Rs. I forgot to pack my thermos.

The Taj Express stops in Mathura only for three minutes, and a large group has piled up their suitcases in the door. They notice my concern and make way for me to move to the next door. After I get down, I notice someone has been calling me on the phone, and before I can answer, a smiling young man says my name — actually a word that sounds “enough” like Mariellen for me to know it’s Pupendra, the person I am supposed to meet. He takes my bags and we walk a long distance down the train platform to the car park, where masses of green-and-yellow autorickshaws are waiting.

I notice they are larger than their Delhi counterparts, and many are decorated with leather applique of large flowers. I wonder if this is a good sign. Pupendra tells me Vrindavan is “a special place, best place in India, most sacred city.” Then he hands me over to his friend, whose name sounds like Sagar, and whose auto is perhaps somewhat less “smart” than the others. Sagar is going to take me to Gopinath Bhavan in Vrindavan, where I’m staying.

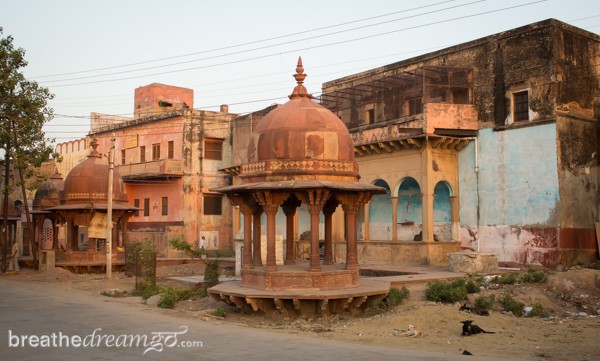

It’s a long, hot, dusty bumpy ride — first out of Mathura and then through a stretch of country side and into Vrindavan, which does seem a bit different than your typical Indian town. We drive down narrow cobbled streets, and everything is dry and dusty and a kind of pale ochre colour that reminds me of Italian Renaissance paintings.

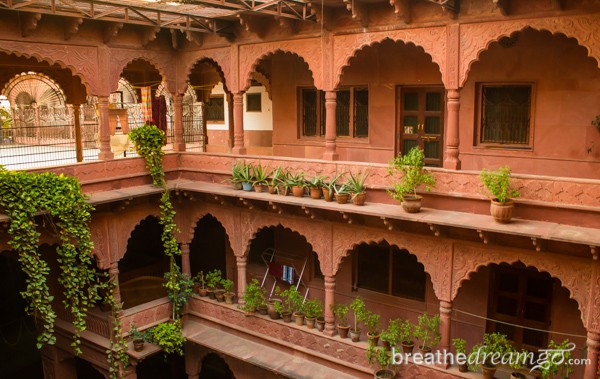

Finally, the river Yamuna appears on our left and we drive along a narrow road with a line of intricately carved temples and ashrams on the right, facing the water. Some of the buildings are quite lovely, with cupolas and spires and carved facades. We stop at one of the loveliest, a large three-story building made of deep rose sandstone and carved in traditional haveli style. This is Gopinath Bhavan, a ladies ashram in Vrindavan that looks old but is actually quite a new building. Out front, cows are gathering to drink, I see monkeys above in the single tree, and groups of devotees walking, barefoot.

Inside, the courtyard is cooler and rosy-hued, with some plants and flowers hanging down from the balconies. I am met by Tungavidya Dasi, who I only know from Facebook, and she signs me in and shows me my room. I’m very happy to meet her in person, she is a warm and sweet-faced Dutch woman with white hair in a pale sari.

I’m on the top floor with a view of the river and the Parikrama Road — the road the devotees walk along as they do their circle of the town. The room is really a small apartment with some Indian furniture and an Indian-style kitchen and bathroom. It has a screened-in balcony — the whole place is monkey proof — and reasonably comfortable, but it needs a good cleaning. Tungavidya kindly arranges the cleaning and supplies me with sheets and a towel while I go out to find the ISKCON Temple and eat lunch at Govinda’s restaurant.

At Govinda’s, I eat a big vegetarian lunch, in the company of a Russian woman who looks, with her round face and head scarf, like a stereotypical Russian peasant woman. She tells me she’s been coming here for 25 years, and she explains the food I am eating is not Indian, it’s Vedic. The waiter has fixed up to bring me a thali, though it’s not on the menu. I get a little of everything, and it’s very good, followed by their signature herbal tea, a rich and satisfying drink.

Though having seen only a bit of the town and not really experiencing it — especially not the spiritual side of Vrindavan — I am wondering what the attraction is. The auto drivers, the usual touts, and others who work in these kinds of tourist and pilgrim centres all seem alike, and Vrindavan is no exception. They try and get as much money as they can from you, they happily give you misinformation and they seem, for the most part, apathetic.

After failing to buy an umbrella and finding only empty ATMs, I go back to the ashram with almonds, water and Limca, very happy to see my room cleaned, and I promptly fall sound asleep. Which seems like the sensible thing to do between 2 and 4 pm, when the sun is baking hot.

At 5 pm, the scene outside my window seems milder, the long slanting rays adding a picturesque quality to the Indian version of Canterbury Tales. It’s time for me to find the Mirabai Temple, so I grab my camera bag, make sure I am monkey proof and headed out into the melee.

Walking in the heat and dust, avoiding the cows, cow shit, pilgrims, monkeys, bicycles and autos, trying to keep ahead of the touts and finding people who could point me in the direction of the Mirabai Temple is quite trying. The narrow river and few dusty trees supply very little respite.

After walking for about 15 minutes and asking many people, I find myself in a narrow, ancient street. A sewage drain runs down the side of the cobbled lane, brick shows through the crumbling ochre-tinged plaster, scalloped door frames surround heavy, wood doors, and again I am reminded of medieval Europe — except with monkeys and eastern architecture. Finally, a small sign, and a door to an even narrower lane. Another false start, another tribe of menacing monkeys, and I find it.

Through a rusty gate and I’m in a small, cool, serene, blue-and-white courtyard. Charming, fresh and modest, the Mirabai Temple is more like a home. A small group of Indian pilgrims sit in front of a grate where a white bearded man is talking to them. They are all very engaged. Unfortunately, it’s Hindi and I understand only a fraction. However, the bearded man speaks English and agrees to repeat what he’s said.

He explains that his ancestor built this home for Mirabai, five centuries ago, and she lived here in this spot for 15 years, before going to Dwarka. I am absolutely delighted to find such a charming spot and such an articulate, open and fascinating man. I can’t believe that I have been so lucky on the very first day of my pilgrimage expedition.

I take photos and a short video and realize I have not brought a notebook. I tell the man I will be back tomorrow to interview him and I leave at sunset. As I walk back along the busy road, I take a detour along the river bank, avoiding the monkeys but putting myself in the way of the river boat touts. It’s worth it to take some stunning photos of the huge orange ball of the sun sinking into the river, and the colourful small boats gliding along the surface. A boy rides a huge black water buffalo across the river and as I take a video they suddenly emerge right in my path and I run.

Everywhere, there are animals and people in this dry landscape. A manic, naked holy man suddenly appears and runs down to the boats. He is wearing only a Brahmin’s thread. He doesn’t surprise me at all.

I pick my way carefully back to the ashram and dive into the quiet and safety of my room — which luckily, and surprisingly, has an A/C unit — to think about my day.

I realize that I desperately need a sanctuary to be in India, I can only expose myself to the heat and the crowds and the challenges and the noise for so long. It’s hard on my nerves, and it’s also emotionally draining.

During lunch at Govinda’s, I listened to the Russian woman talk about Vrindavan, and the mythical lore of this place — where Krishna and his gopis cavorted on the river bank — with bemusement. The classical image of pastoral, lush and harmonious Vrindavan are so far removed from the dirty, polluted, over-crowded, dry, monkey-menaced, scorched-earth reality of today that it’s shocking.

I read that Mirabai was also shocked when she arrived in Vrindavan in the mid 17-th century because she didn’t expect any buildings. She too was expecting a pastoral paradise. Is this what faith is all about? That we hold up an ideal to hang onto in the face of the disappointments of reality?

Anyway, I’m here, and I’m lonely, and I don’t love Vrindavan, I don’t feel I have found a sanctuary, and I’m not sure what I’m doing here. Except dedicating myself to the discipline of the pilgrimage, to stick with it, and go through whatever ups-and-downs, emotional roller coasters and life lessons are in store for me. Perhaps this is my first glimpse into what it may have been like for Mirabai — to leave the comfort and safety of home to follow her heart and the call of her soul.

The Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan

I wake in Vrindavan.

I wake with two problems on my mind: money and food. I slept without dinner and no breakfast is available; and the day before, I tried two ATMs and both were out of money. So, with a mixture of hope and trepidation, I haggle for an auto and go straight to the ATM. The sound of the money dispensing is more delightful to me than all the temple bells in this moment. Even in a holy city like Vindravan, money is necessary.

From there I go directly to Govinda’s Restaurant at the ISKCON Temple for breakfast. As it is an “ekadasi day” — a day without grains — I have a strange breakfast of fruit, juice, a mango lassi and kind of potato dosa. Then I have their thick herbal tea and a coconut laddu.

With money in my wallet and food in my tummy, I feel so much better about life and about the day. These things do matter, and I don’t agree with the spiritual people who turn their backs on embodied life. In Vrindavan, I find myself thinking that if all the effort that goes into prayer, darshan, and parikrama were put into cleaning up the city, creating an irrigation system so more plants and trees can grow, installing proper plumbing, sterilizing the stray dogs, educating all the children, and addressing all the other social and environmental problems, than you would have a much more lovely, harmonious Vrindavan — the kind in myth and legend.

But in the meantime, it’s a very crowded, dirty, dusty place — no different to me than any other Indian town. I hail a bicycle rickshaw outside ISKCON and fall into the usual negotiations over the price. They say 100 rupees, which is two or three times the price that Indians pay. A young woman joins in and bargains one driver down to 50 rupees to take me to the Mirabai temple. He stops and buys two small bags of water from a street stall.

We ride through a long, narrow market area — it’s fascinating to see the stores, the old buildings, some carved, and the crazy traffic jams. Bullock carts, a camel cart, every type of vehicle, all vying for space in a very narrow street. We pass tiny children playing and open-air barbers and groups of devotees walking parikrama in their bare feet. Finally, we get there. Because of the distance and the heat, and the man’s advancing age, I decide to give him 100 rupees after all. He isn’t sure whether I mean for him to keep it. I feel his sweetness and humility in my heart, I feel humbled.

Immediately on stepping through the old, rusty gate, and entering the small residential temple, I feel cooler and calmer. I love the feeling in this shady, airy house, full of light and greenery, painted pale blue and white. The bearded man appears, this time in a more priestly garb, a white robe trimmed in red, and we sit down to talk.

He gives me a piece of paper, tells me it’s at least 45 years old, and that I should have it translated and copied. On it, he has carefully printed his name and address:

Praduman Pratapsingh,

Meerabai Temple

Govind Bagh, Vrindaban

Praduman tells me, in simple English, what’s written on the paper, which is in Hindi. He goes through the main details of Meerabai’s life, and how she was rejected by her husband’s family because of her devotion to Krishna, her dancing and singing. This is why she came to Vrindavan — to find peace and to devote her life to Krishna.

Praduman’s ancestor built this temple for her to live in, and she lived here for about 15 years. Apparently she wrote many poems in this temple. He continues to tell me her life story. Meerabai went from Vrindavan to Dwarka. While she was living in Dwarka, when she was about my age (around 50), there was a drought in Rajasthan. Some of her family members travelled to Dwarka to entreat Meerabai to return, but she refused. That night, according to Praduman, she dissolved in Lord Krishna — and the drought ended.

Praduman talks about Meerabai with conviction and enthusiasm, and though he must do this several times every day, he seems very passionate. He has an open face, large eyes, and he is very expressive. He is very accommodating to me, and shows me around the temple, poses for me and even opens the altar grate so I can photograph the statues. He tells me that he is the ninth generation of his family to be born here, and to maintain the temple. He has a son and daughter — they are the 10th generation (but his son is an artist and animator in Mumbai).

“People come here for peace, love and spiritual strength,” Praduman says. “This is the real place of Meerabai. She lives in this temple. People who come here can feel Meerabai and Gopal (Krishna) in their hearts.”

Though I am not a Krishna (Gopal) devotee, I do feel a light, happy atmosphere in this temple. It’s a great start to my Meerabai expedition to find this lovely temple and this warm and helpful man.

I wake up on the third day of the Mirabai expedition feeling satisfied. Meeting Praduman and basking in the delightful energy of the Mirabai Temple is such a great start.

I’m also very grateful for the opportunity to stay at Gopinath Bhavan. It is a lovely red sandstone building, run by warm women, most of whom come from European countries such as France and Holland. They gave me a top floor room with a view of the Yamuna River, and the Parikrama parade. I slept very well on a simple bed, and had the luxury of an AC unit in my room.

Nevertheless, I find Vrindavan a difficult place. Very hot and dusty, menaced by grabby monkeys, stray dogs, wild pigs, cows and the natural substances they leave behind, and filled with auto drivers who try to extract maximum cash from foreigners as a matter of course.

Vrindavan in myth and legend is a fecund place of peace and harmony, a kind of garden-of-Eden where Krishna and his gopis (milk maids) cavorted in innocence, bathed in love. Vrindavan in reality cannot be further from this image. It must take enormous faith for the many devotees who flock here to feel the spiritual energy of this place.

I feel a bit bad about not feeling Krishna’s energy in Vrindavan. But when I was discussing the Mirabai expedition with a woman I met at Gopinath Bhavan, she said it’s great that I am giving attention to one of the female players in the Krishna story. So be it.

I am happy to move on.

I decide to leave early on my third day in Vrindavan. I have to be in Agra to take the train to Rajasthan at 5 p.m., so I make plans for a taxi to drive me there in the late morning. I consider seeing the Taj Mahal (for the third time), and decide to stop at the ITC Mughal hotel. I stayed here previously for a few days so it feels a bit like a homecoming.

I get a warm reception from Jyoti, the PR Director, who invites me for lunch with her in Peshawar, their signature restaurant. She offers me a room to get refreshed, and I swim in the pool, instead of seeing the Taj Mahal.

The Mirabai expedition takes an unplanned detour into luxury and it feels right, too. Mirabai was a princess who lived in a sumptuous palace before striking out on her own, to both escape the cruelty of her husband’s family, and to follow the voice of her soul, the call of her devotion to Krishna. There is synchronicity in this visit too, as the ITC Mughal celebrates the era of Emperor Akbar — who visited Mirabai in disguise, and praised her talent and devotion, bestowing upon her a valuable necklace.

So, as Mirabai left her palace home, I have to leave the comfort of the ITC Mughal to brave the chaos of the Agra train station. Upon arriving by taxi, I try and negotiate a porter to carry my bags to the somewhat distant platform and help me find my berth, but the female (!) porter demand 350 rupees, probably three or four times the regular rate. Luckily, I never carry more luggage than I can handle in India, so I grab my bags and find my platform myself.

A broken heart, a spiritual journey

The train is late, but eventually it arrives, I find my berth and settle in for the journey to Ajmer in Rajasthan. I’m in a lower berth, in the second-class compartment. Though it is not that clean, the bathrooms are a bit scary and I am surrounded by Indian men burping and snoring, somehow I like taking the train in India. I like the gentle movement and knowing I am going somewhere fascinating — plus I like it better than driving. The roads in India are a chaotic obstacle course and you really do feel you are taking your life in your hands.

Somehow, the movement of the train makes me philosophical. I started out on the Mirabai expedition with feelings of sadness and vulnerability. I didn’t like Vrindavan, I doubted my self and the expedition and I was missing my friends in Delhi.

I am wondering why am I travelling at all? Unlike Mirabai, I was not rejected and threatened by my family, though I did feel abandoned as a teenager after my parents divorced; and again after my parents died. But I still have my siblings and their families at home in Canada.

Heartache was one of the things that originally propelled my travels in India. Heartache also propelled my spiritual longing. But I think, perhaps, my heart is finally mending.

In Vrindavan, surrounded by bhaktis, I realized I want to live in the world. I don’t want to reject the embodied experience. I like a clean and aesthetically pleasing environment, a touch of luxury, some jewelry and makeup.

Some of the women devotees in Vrindavan seem to delight in dressing up in saris and looking pretty, reminding me of Krishna’s gopis; but others seem so thin and colourless, and I find myself concerned about them.

There must be a way to be spiritually aware and yet of this world. I would love to see spirituality and materialism come together, so that people increase their consciousness about daily life, about use of resources, garbage disposal, how we treat animals, the planet and each other; and also continue to enjoy the sensuality of life, and the aesthetics of art and nature.

I take out my iPad, to read The Great Railway Bazaar by Paul Theroux (perfect reading for a train journey in India). I’m on this train until I arrive in Ajmer at about 1:15 a.m. Though I have made careful plans, to have a reliable and reputable driver waiting for me on the train platform, it is always unnerving to arrive late at night at a train station in India.

Continue reading about the Mirabai Expedition on Breathedreamgo:

Part 2: Uncovering the feminine in Merta, Rajasthan

Part 3: The footsteps of royalty in Chittorgarh, Rajasthan

Part 4: Releasing the bonds of love in Dwarka, Gujarat

Photo credits

- Photo credit: GR Sharma

If you enjoyed this post, you can….

Sign up to The Travel Newsletter in the sidebar and follow Breathedreamgo on all social media platforms including Instagram, TripAdvisor, Facebook, Pinterest, and Twitter. Thank you!